Decoding the Pluribus Signal

The Signal

If you’re unaware, Pluribus is a character drama that takes place in an expertly-concieved science fiction facsimile of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Go watch it. We open the series with a signal arriving from outer space. Scientific excitement - it’s the WOW! signal only it’s stronger, more consistent, and very clearly artificial in origin. How would someone transmit a signal all that way? How much data could you feasibly transmit from that great a distance? What could it possibly contain? What would it take for us to transmit a similar signal?

The signal was observed at the Very Large Array, which you’ll recognize from the dramatic shots of giant satellite dishes in the desert. I took some notes as they described it:

- “It’s this wide!!”, with the actor holding his fingers about a centimeter apart

- Emanating from Kepler 22, 640 light years away

- Periodic and repeating

- Quaternary pattern in the data

- 78 second interval

- Drifting, or walking the EM spectrum

- Observed at the Very Large Array in New Mexico

The VLA can observe from 54Mhz-50Ghz, but it’s typically tuned like a radio to observe 1-2Ghz of spectrum at a time, and is pointed at specific things in the sky. If we’re using the VLA to look at Kepler-22, it could be to look for evidence of a magnetosphere on the planet, or to determine if there are solar flares, or maybe just to tune the telescope to look at something farther away in that same direction.

No matter the case, at the VLA, there’s a program called COSMIC that searches for technosignatures in parallel with other scientific observations. It works by splitting the signal from the telescopes and sending it to a separate facility for post-processing. Whenever the VLA is making an observation, if there is something in the data that suggests it’s artificial in origin, we’ll find it!

From the initial observations we don’t really get a strong sense of frequency, amplitude, or directionality. But as soon as the team there determines that it’s a description of DNA’s four bases, we get a useful image. I took a couple of photos and have superimposed them.

From the screenshot we can also see that we received three ‘symbols’ of information in 0.018 seconds, or 0.006s per symbol. That’s a baud rate of 166.67 symbols per second. Over 78 seconds, we would receive exactly 13,000 symbols before the signal repeats. A quaternary pattern means each symbol contains two bits of information, twice binary. The data rate is thus very small, 333.33 bits per second, with no error correction in evidence other than the fact that it repeats. In interstellar space, throughput is difficult to come by. This message is just 3.25kb.

At this point the scientists have figured out that the “quaternary pattern” is representing DNA bases. We can also see that pulses of equal length arrive on slight frequency offsets within the signal. This is called Frequency Shift Keying and is a simple form of signal modulation. It requires high power to transmit, and high bandwidth to collect and decode, but messages are less likely to suffer from interference. You don’t need to encode the data with error correction or other information that would make your message harder to decipher. And perhaps most importantly, it’s unmistakably artificial.

The DNA

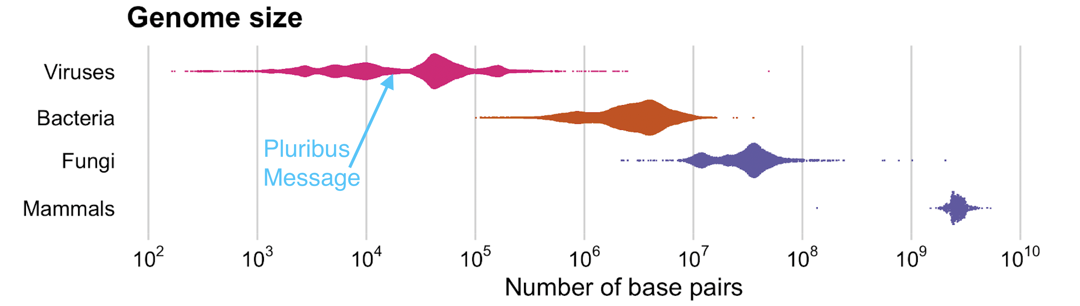

The message contains DNA, the building blocks of life on Earth and apparently, the Milky Way Galaxy too. We got a message from the sky and were able to decode it, but is 13,000 bases a useful payload? The two questions that come to mind are first whether it’s possible at all to fit a living thing into such a small message, and second whether it’s plausible that any DNA-based payload can cause such an extreme neurological effect.

Let’s take a look at some across various families of life on earth. Mammals have several billion bases, while bacteria start around 100 kilobases (100kb). Viruses code pretty small, though! Pappilomaviruses fit in 5kb. HIV and Rabies are 10kb and 11kb respectively. The CRISPR-CAS9 protein requires 4.1kb, but it’s presumed that the recipient of this message can insert their own. Most genes require around 3kb. The COVID spike protein, mankind’s most sophisticated genetic engineering achievement, has 28kb. These examples show that a virus or some sort of biological nanomachine can fit inside the message we receive from Kepler-22, but what could it achieve, once sent?

Genetics is complex. There are thousands of disorders caused by single-letter mutations. The instructions used by CRISPR-CAS9 to find and insert DNA require only 400 bases. We’re at the start of our genetic understanding, but there are plenty of small mutations that cause massively outsided effects. There’s also precedent in nature for complex behaviors being motivated by viruses, and for viruses to be transmissible across species boundaries. Rabies is a good analogue for what we see in Pluribus. It’s transmitted via contact with mucus membranes and it causes a relatively complex set of behavioral changes. Fear of water, loss of sleep, aggression. Toxoplasma Gondii, while not a virus, is another good example. It can infect pretty much every animal species on Earth, and in humans is associated with schizophrenia, traffic accidents, rule-breaking, and a host of other behaviors. Ophiocordyceps unilateralis compels its host (an ant) to climb up somewhere high and die so that spores can be spread more effectively. Those have genomes around 60 and 20 million bases, too large to fit in a transmission, but they are useful examples of how the machinery of life can act in parasitic ways to the detriment of a host.

The notion of a population-level virus and the specific behaviors caused by the virus in Pluribus raises a lot of questions, and yields a lot of narrative potential. Why does all of humanity act the same way? Why have they all become so docile and truthful? Why are they building a giant transmitter? Why (and how) do they coordinate with their own brainwaves? These are all really big behavioral shifts, far bigger than things we know are possible with such a small amount of DNA, with some aspects of their behavior simply being outside the realm of possibility. But the concept of biology causing behavioral changes is sound.

On Earth today, viruses aren’t alive and don’t really have a purpose except to transmit themselves. The host of a virus is a single creature, with the population of creatures providing a reservoir for the virus to exist in perpetuity. The idea that we might have a civilization-level DNA-techno-virus that was created and exists solely to propagate itself aligns pretty closely with the behavior of viruses in the real world. What would it take to transmit it?

Transmitting DNA Into Outer Space

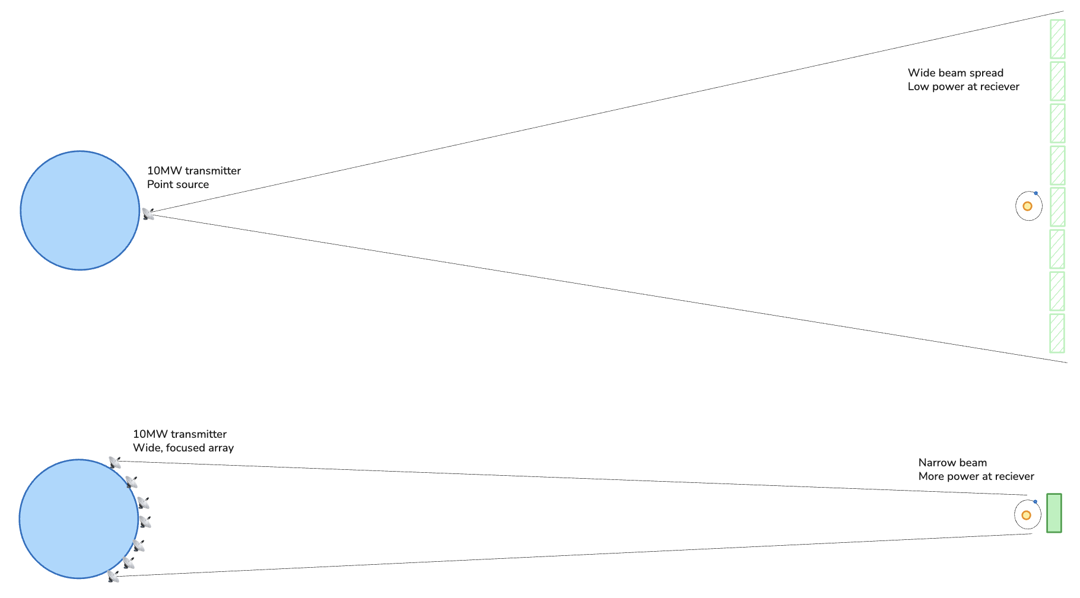

At the start of the show one of the scientists says they’d need a transmitter the size of Africa for us to receive a message of this nature. This has to do with the way that signals are propagated into space. We’ve been broadcasting radio for a little over 100 years now, so you might think the Earth’s radio bubble is 100 light years into space. And it is, but after about 10 light years, those broadcasts have so little energy that they are indistinguishable from the cosmic microwave background. They’re impossible to see unless you had a massive antenna and were looking right at us. You would need a transmitter the size of Africa to get a signal Kepler-22 to Earth, if you were broadcasting to everyone in the galaxy. But if you target another star directly, you can get away with a much smaller configuration.

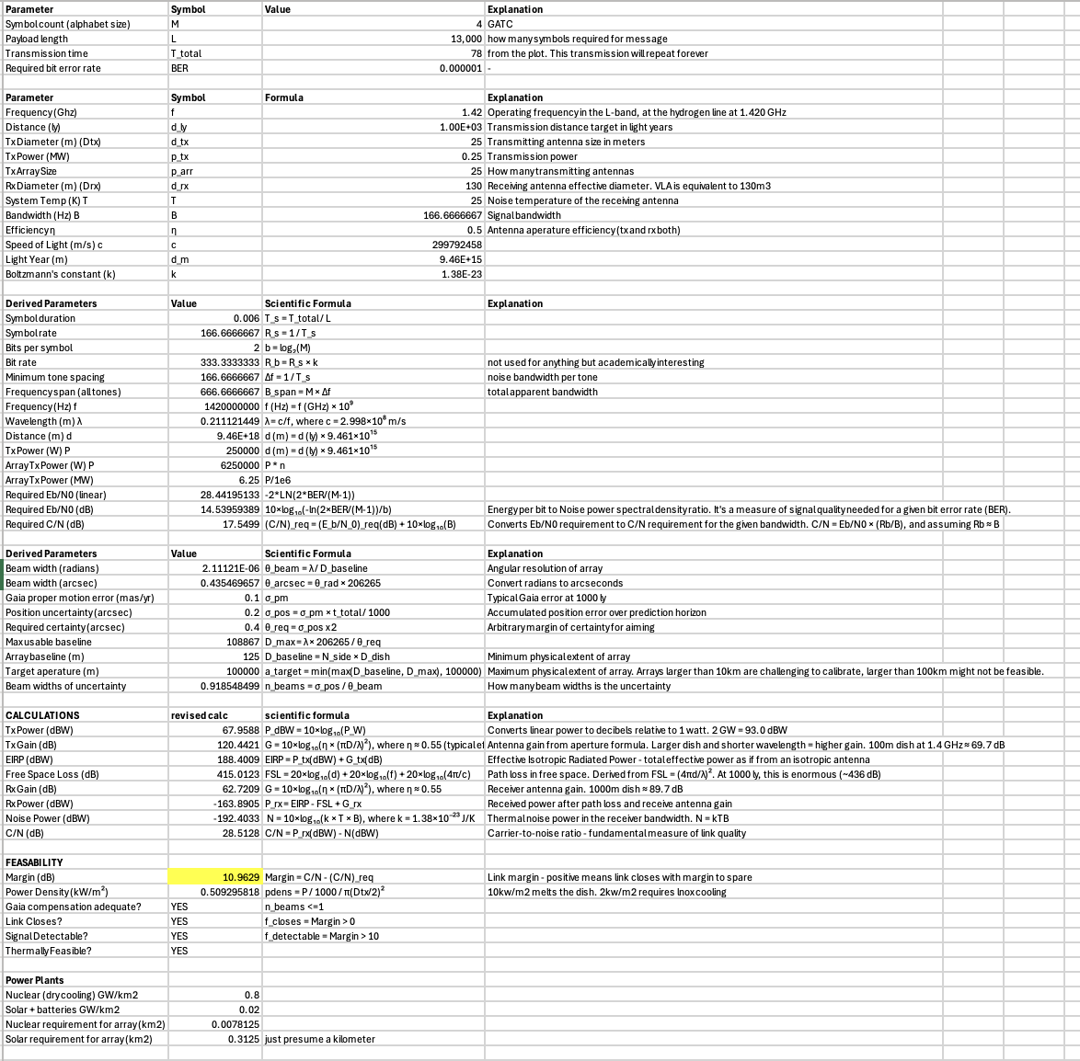

Our transmitter needs to focus its beam in order to maintain power over long distances. I modeled the link budget for a connection between Earth and Kepler-22 using a transmitter array that is very much like the VLA in New Mexico. A ’link budget’ is how we compute the transmit power necessary for a signal to traverse a distance, reach a receiver, be detectable, and be decoded without error. The keys for us are beam focus and raw power. We need to transmit as tight of a signal as possible, using the largest practical array we can.

Using an array of 25 VLA-sized transmitters (25m each), with each broadcasting at 250kW for 6.25MW total, in a configuration with a 100km diameter, we can get a signal to a star 1000 light years away with 10db of margin. Meaning the signal will be loud and unmistakably artificial. Now, there are some liberties here. 250kW is five times the maximum power authorized to any AM radio station in the US, and we’re talking about running 25 of these. This is a lot of power! And a 100km array configuration presents significant calibration concerns, requiring space-based interferometry to maintain calibration through atmospheric variations. There are constraints, too. If we try shrinking the array down to 10km diameter, we need either 1000 times as many transmitters or 100 times as much power to get the job done. And if we try to cross the Milky Way - on the order of 100,000 light years, we need a 100 million times the power.

This is a tightly constrained problem but not anything that’s too far outside of our current technological capabilities today. Where it gets a little more challenging, perhaps, is when we try to scale this up to reach as many stars as possible.

Transmitting To All of the Stars

There are 100-400 billion stars in the Milky Way Galaxy, exactly one of which is known to host life. If we’re sending a message like this, we’re operating under a new, focused set of assumptions. Most specifically we are assuming that scientists exist on other planets, around other stars, and that the chemistry and composition of their life is the same as ours. This is amazing, because it allows us to narrow this list down from 250 billion stars to something that is hopefully more manageable.

The ESA’s Gaia program is our best effort at building a complete database of these stars. It contains information about the stars’ apparent motion, their metallicity, temperature, whether they’re in a binary system, and lots more. The layout of the catalog looks something like this:

| Stars | Count |

|---|---|

| Estimated Total | 250,000,000,000 |

| In Gaia Catalog | 1,811,709,771 |

| Location Known | 192,208,822 |

| Likely Habitable | 31,601,510 |

We’ve only surveyed about 1% of the estimated total stars in the Milky Way. Of those, we know the location and apparent motion of around 10%. That’s the first filter - stars we don’t know about, and stars we can’t yet place with accuracy.

My filters for habitability are fairly liberal - I filter to sun-like temperatures, in the main sequence, with solar metallicity of 0.3-3x our Sun. I exclude binary star systems, stars that are obscured by lots of dust, and photometrically variable stars (stars with lots of activity that might be harmful to life). This cuts us down to 31.6 million candidate stars.

Most of the habitable stars we know about are 3-5k light years away from us for reasons that aren’t apparent to me, but recall that we can’t really transmit beyond 1000 light years anyways. We could instead constrain our transmissions within 1000 light years and build multiple arrays of transmitters in order to contact all our local neighbors. One per nearby habitable star. And there aren’t that many! Only 756,795.

| Distance (ly) | All Stars | Habitable Stars | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 81 | 5,323 | 371 | 7% |

| 163 | 51,970 | 3,044 | 6% |

| 244 | 209,535 | 10,684 | 5% |

| 570 | 2,609,253 | 144,162 | 6% |

| 1059 | 10,363,073 | 745,740 | 7% |

| 2526 | 46,261,477 | 6,608,351 | 14% |

| 5053 | 106,699,514 | 21,815,587 | 20% |

| 10024 | 173,518,074 | 30,651,842 | 18% |

| all | 192,208,822 | 31,601,510 | 16% |

Transmitting to 756k stars would take all of the power on Earth and then some, but Pluribus has some plot magic to help. All of Earth’s 7.3 billion people are committed to the task simultaneously. Our single-star array requires 6.5MW to aim a high-quality beam at a neighboring star. Earth, in total, has around 3TW of total power capacity. With our existing power infrastructure, optimistically we’d be able to run around 450,000 of these transmitters at once. This is enough to reach 70% of the nearby candidate stars. The land requirements for these arrays is pretty minimal - while the arrays themselves are spaced out to quite a large diameter (100km), there is no requirement that we can’t interleave arrays and point them at different stars. The actual land requirement is less than 1km^2 per array.

If we wanted to target more stars we could build arrays of solar panels for each array of transmitters - the panels plus a battery for 24x7 require another 1km^2 of area. Just 2km^2 in total of land on earth for each star system we wish to target. We have more than enough desert to host all of these, anywhere on Earth. The limiting factor would be our ability to manufacture a transmission infrastructure that self-sustains for hundreds or thousands of years after the virus consumes all of the humans on the planet. Today’s solar panels last about 20 years but they could easily last hundreds with higher-quality casing and coatings. Maybe a geothermal plant could last for longer? Our modern society is only just starting to think about building deliberately enduring structures.

I’ve established that it’s plausible to transmit a message to every habitable star within a thousand light years, and possibly even more, if we marshal all the resources of humanity to do it. Will anybody be listening?

Civilization-Ending Viruses and the Fermi Paradox

The most unusual aspect of Pluribus isn’t what the signal does or what the characters do about it, it’s what the presence and form of the signal says about our universe. There’s this principle, the Copernican principle, that suggests that everything about Earth and life and Humanity is totally typical. This is the idea that removed ego from the study of the stars and enabled us to understand what little we do today. But the signal in Pluribus is nearby - only 640 light years. And it’s comprised of recognizable DNA. And it seems to be a weapon. While the show is mostly focused on the events taking place in Carol’s Albuquerque cul-de-sac, the interstellar it’s taking place in is one in which life is far more familiar abundant than we currently know it to be. Even the signal itself can’t be presumed to be unique! If even one is known and shown to exist, the haste with which we discovered it suggests strongly that many do, and there are many civilizations available to carry it forward.

Taking the Copernican principle to its logical extreme, the presence of the signal so close to Earth implies that our galaxy has a minimum of two civilizations per 137 million cubic light years (1.37 * 10^8). That’s the volume of the sphere between Earth and Kepler-22, where two completely typical technological civilizations exchanged a message. This is a surprisingly large fraction of the total volume of the Milky Way. Excluding its volatile core, the Milky Way contains an estimated 5 trillion cubic light years (5.29 * 10^12). Which means a lower bound on the number of civilizations in the galaxy is 38,600. And if that is the case, Earth’s 1000-light-year broadcast cone will encounter and potentially infect 1.81 additional civilizations, long after its own civilization perishes.

Illustrated concept of killer technoviruses propagating through the Milky Way.

Where did something like this come from? The coding as DNA suggests generations of civilizations before us with knowledge of the nature of life in the universe. It’s possible to imagine a conflict breaking out over interstellar distances. Even at interplanetary distances the amount of destructive potential that any adversary has is immense and frightening. A weapon that compels your enemy to willfully destroy themselves is far preferable to a weapon that destroys the planet and the resources that you’re fighting over. This feels like a flavor of mutually assured destruction adapted for the complexity and nuance of interstellar warfare and interstellar colonization.

Is Pluribus going to give us an invasion fleet? Doubtful. The tension of the show builds from the isolation and the immensity that two people experience as they face off against a mutated remainder of humanity. Aliens would detract from an altogether human story. But if Carol and Manousos somehow manage to save the world, they’ll be a part of a different universe than they started with. When the survivors look to the cosmos with a new purpose and a new perspective, hopefully they’ll have the good sense to listen more carefully.